The Marriage of

Prophet Muhammad ﷺ

and Aisha ؓ

Contextualizing Marriage Practices in Pre-Modern Societies

The Marriage of

Prophet Muhammad ﷺ

and Aisha ؓ

Contextualizing Marriage Practices in Pre-Modern Societies

The Marriage of

Prophet Muhammad ﷺ

and Aisha ؓ

Contextualizing Marriage Practices in Pre-Modern Societies

The Marriage of

Prophet Muhammad ﷺ

and Aisha ؓ

Contextualizing Marriage Practices in Pre-Modern Societies

The Marriage of

Prophet Muhammad ؐ

and Aisha ؓ

Contextualizing Marriage Practices in Pre-Modern Societies

Abstract

Abstract

This whitepaper offers a nuanced, cross-cultural analysis of how life expectancy and social norms in pre-modern societies influenced marriage practices. Primarily focusing on Western traditions, it links changes in demographic shifts to marital customs and societal expectations. Drawing parallels between these traditions and Islamic practices, it examines the marriage between Aisha B and Prophet Muhammad A within this broader historical context.

This whitepaper offers a nuanced, cross-cultural analysis of how life expectancy and social norms in pre-modern societies influenced marriage practices. Primarily focusing on Western traditions, it links changes in demographic shifts to marital customs and societal expectations. Drawing parallels between these traditions and Islamic practices, it examines the marriage between Aisha B and Prophet Muhammad A within this broader historical context.

1

How Life Expectancy Shaped Marriage Trends

How Life Expectancy Shaped Marriage Trends

From Old Worlds to New Norms

From Old Worlds to New Norms

Life Expectancy in Early Societies

Life Expectancy in Early Societies

Marriage patterns in pre-modern societies were shaped by life expectancy in ways that starkly contrast with modern practices. In the pre-modern world, average life expectancy was significantly lower, generally ranging from 25 – 40 years[1]. This was mainly due to high rates of infant mortality, malnutrition, childbirth complications, frequent conflicts, and the prevalence of infectious diseases. For example, life expectancy in Ancient Greece and Rome was estimated between 25 – 30 years[2]. Even as late as the Middle Ages, average life expectancy hovered around 30 – 33 years[3]. This shorter lifespan placed immense pressure on communities to ensure the survival of future generations, which significantly influenced social norms around marriage.

Women, in particular, faced greater urgency to marry and bear children soon after reaching puberty, not simply as a biological marker of maturity but as a pragmatic response to maximize fertility in an era of high infant mortality. Mary T. Boatwright, a distinguished historian and Professor of Classical Studies at Duke University, observes in her book Imperial Women of Rome, “since only half of children born would survive childhood, women had to give birth five to six times for Rome’s population rate to remain steady"[4]. High infant mortality and shorter life spans meant maintaining population levels was critical, as dwindling numbers threatened both resources and defense against external threats.

Early marriage was therefore not only a cultural norm, but a social responsibility for the survival of the community and the economic stability of households. Women were often married younger than men because their shorter life expectancy (in part due to childbirth risks), left them with limited time to bear and raise children. Meanwhile, men often delayed marriage until they had established economic or social stability before forming families[5].

Marriage patterns in pre-modern societies were shaped by life expectancy in ways that starkly contrast with modern practices. In the pre-modern world, average life expectancy was significantly lower, generally ranging from 25 – 40 years[1]. This was mainly due to high rates of infant mortality, malnutrition, childbirth complications, frequent conflicts, and the prevalence of infectious diseases. For example, life expectancy in Ancient Greece and Rome was estimated between 25 – 30 years[2]. Even as late as the Middle Ages, average life expectancy hovered around 30 – 33 years[3]. This shorter lifespan placed immense pressure on communities to ensure the survival of future generations, which significantly influenced social norms around marriage.

Women, in particular, faced greater urgency to marry and bear children soon after reaching puberty, not simply as a biological marker of maturity but as a pragmatic response to maximize fertility in an era of high infant mortality. Mary T. Boatwright, a distinguished historian and Professor of Classical Studies at Duke University, observes in her book Imperial Women of Rome, “since only half of children born would survive childhood, women had to give birth five to six times for Rome’s population rate to remain steady"[4]. High infant mortality and shorter life spans meant maintaining population levels was critical, as dwindling numbers threatened both resources and defense against external threats.

Early marriage was therefore not only a cultural norm, but a social responsibility for the survival of the community and the economic stability of households. Women were often married younger than men because their shorter life expectancy (in part due to childbirth risks), left them with limited time to bear and raise children. Meanwhile, men often delayed marriage until they had established economic or social stability before forming families[5].

Swipe to scroll horizontally

Swipe to scroll horizontally

Evolution of Life Expectancy

Evolution of Life Expectancy

From Pre-Industrial Era to the Present

Well into the 19th century, average life expectancy remained below 40 years in many parts of the world. By the mid-20th century, rapid advancements in healthcare, improved nutrition, and rising living standards extended lifespans in developed nations to 65 – 70 years[7]. Today, many countries have seen life expectancy surpass 80 years, a testament to societal progress.

Well into the 19th century, average life expectancy remained below 40 years in many parts of the world. By the mid-20th century, rapid advancements in healthcare, improved nutrition, and rising living standards extended lifespans in developed nations to 65 – 70 years[7]. Today, many countries have seen life expectancy surpass 80 years, a testament to societal progress.

Shifting Dynamics of Marriage

Shifting Dynamics of Marriage

Longer Lives, Later Marriages

Longer Lives, Later Marriages

The turning point in women’s life expectancy came in the 20th century, when advancements in maternal health, such as antibiotics, prenatal care, and safer childbirth practices, enabled women to live longer than men on average.

This shift, coupled with increased access to education and career opportunities, fundamentally altered social dynamics around marriage and family life. The pressure for early marriage diminished as women gained more autonomy and longer life expectancy, allowing for delayed marriages and smaller family sizes[8].

The turning point in women’s life expectancy came in the 20th century, when advancements in maternal health, such as antibiotics, prenatal care, and safer childbirth practices, enabled women to live longer than men on average.

This shift, coupled with increased access to education and career opportunities, fundamentally altered social dynamics around marriage and family life. The pressure for early marriage diminished as women gained more autonomy and longer life expectancy, allowing for delayed marriages and smaller family sizes[8].

Adolescence as a Distinct Phase of Life

Adolescence as a Distinct Phase of Life

In pre-modern societies, adolescence as a concept did not exist in the structured way we understand it today. The transition from childhood to adulthood was brief, with young people assuming adult responsibilities, such as marriage and childbearing, soon after reaching physical maturity. As one of the world’s bestselling historian of medieval Europe, Frances Gies explains:

In pre-modern societies, adolescence as a concept did not exist in the structured way we understand it today. The transition from childhood to adulthood was brief, with young people assuming adult responsibilities, such as marriage and childbearing, soon after reaching physical maturity. As one of the world’s bestselling historian of medieval Europe, Frances Gies explains:

“Medieval children did not experience the prolonged stage of formalized maturation that modern educational systems have imposed, and children were generally treated as responsible adults from puberty” [9].

“Medieval children did not experience the prolonged stage of formalized maturation that modern educational systems have imposed, and children were generally treated as responsible adults from puberty” [9].

Frances Gies, American Historian

Frances Gies,

American Historian

Marriage and the Family in the Middle Ages

Marriage and the Family

in the Middle Ages

In many pre-modern societies, including ancient Greece and Rome, puberty and marriage often coincided for girls, marking a key transitional point in their lives. As noted by classical scholar Sarah Pomeroy, a leading expert in the social history of women in antiquity, “puberty and marriage often came at about the same time in a girl's life” [10]. Even into the 20th century, the canonical age for marriage in Christian societies was set at twelve — considered by the Church as the age of biological maturity for marriage[11]. In some denominations, betrothals were arranged even earlier, sometimes well before puberty[12].

In many pre-modern societies, including ancient Greece and Rome, puberty and marriage often coincided for girls, marking a key transitional point in their lives. As noted by classical scholar Sarah Pomeroy, a leading expert in the social history of women in antiquity, “puberty and marriage often came at about the same time in a girl's life” [10]. Even into the 20th century, the canonical age for marriage in Christian societies was set at twelve — considered by the Church as the age of biological maturity for marriage[11]. In some denominations, betrothals were arranged even earlier, sometimes well before puberty[12].

Historical and Legal Transformation

The formal concept of adolescence as a distinct phase of life emerged much more recently, alongside the industrial revolution and rising life expectancy. Prior to 1920, the consent ages in the United States allowed young people to marry as early as 10 or 12 with parental consent, with Delaware's minimum age set at 7 years in 1895. These laws reflect a period when shorter life expectancy led to earlier assumptions of societal roles, including marriage.

In modern times, adolescence has evolved into a period of personal and educational growth, with marriage and childbearing often delayed until individuals are well into adulthood. As life expectancy rises, this extended adolescence has become a crucial phase, allowing individuals to prepare for the demands of adulthood in ways unimaginable to earlier societies.

Despite these advancements, age-of-consent laws still vary globally, with countries such as Argentina or Spain still permitting marriages at ages as young as 13 in 2007[13]. This variation underscores the complexities of adolescence and adulthood in different societies, highlighting how legal and cultural norms continue to evolve in response to broader societal changes.

Historical and Legal Transformation

The formal concept of adolescence as a distinct phase of life emerged much more recently, alongside the industrial revolution and rising life expectancy. Prior to 1920, the consent ages in the United States allowed young people to marry as early as 10 or 12 with parental consent, with Delaware's minimum age set at 7 years in 1895. These laws reflect a period when shorter life expectancy led to earlier assumptions of societal roles, including marriage.

In modern times, adolescence has evolved into a period of personal and educational growth, with marriage and childbearing often delayed until individuals are well into adulthood. As life expectancy rises, this extended adolescence has become a crucial phase, allowing individuals to prepare for the demands of adulthood in ways unimaginable to earlier societies.

Despite these advancements, age-of-consent laws still vary globally, with countries such as Argentina or Spain still permitting marriages at ages as young as 13 in 2007[13]. This variation underscores the complexities of adolescence and adulthood in different societies, highlighting how legal and cultural norms continue to evolve in response to broader societal changes.

2

The Evolution of Marriage Norms

The Evolution of Marriage Norms

From Ancient Civilizations to Modern Practices

From Ancient Civilizations to Modern Practices

Marriage Norms in the Ancient World

Marriage Norms in the Ancient World

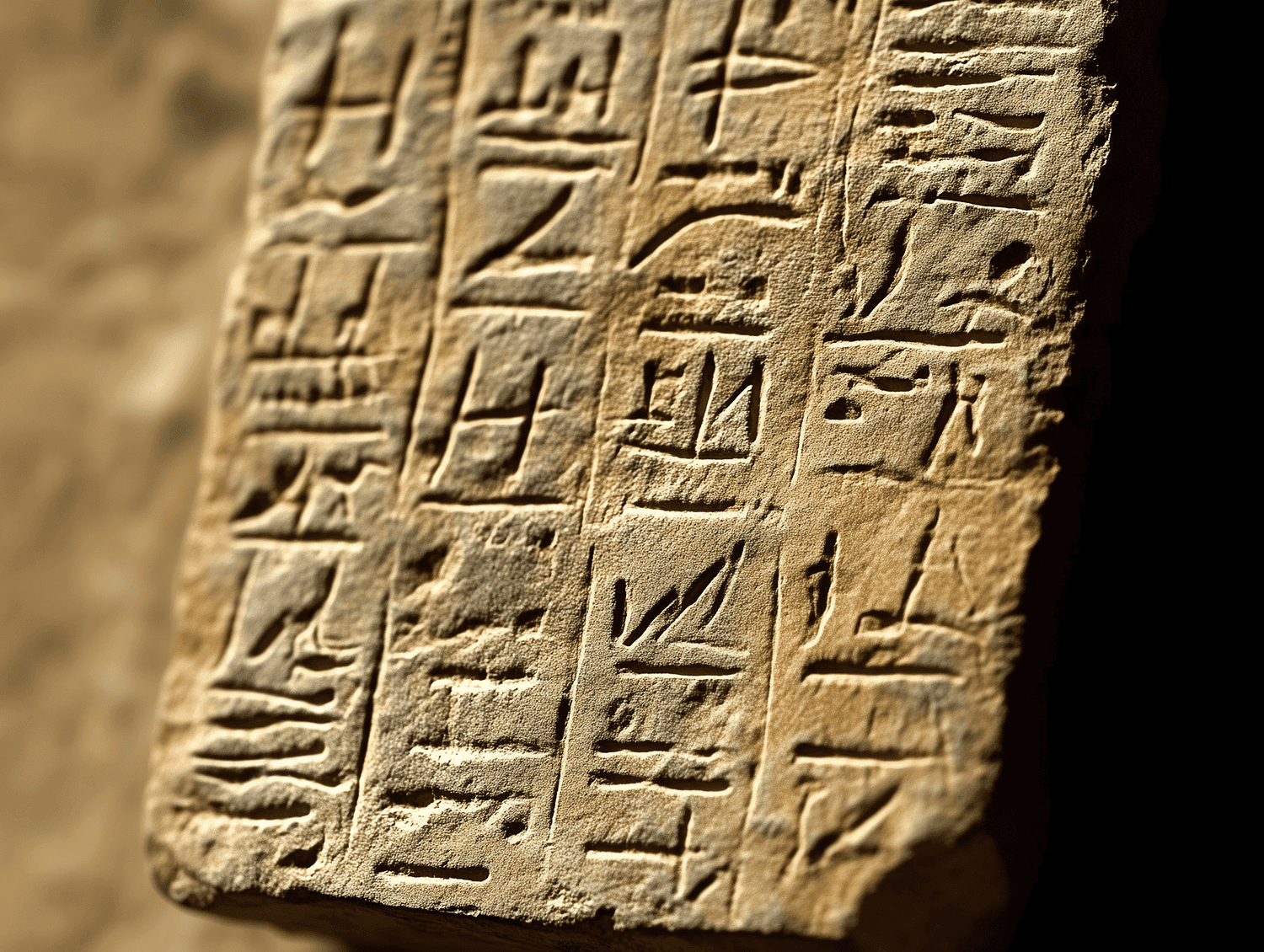

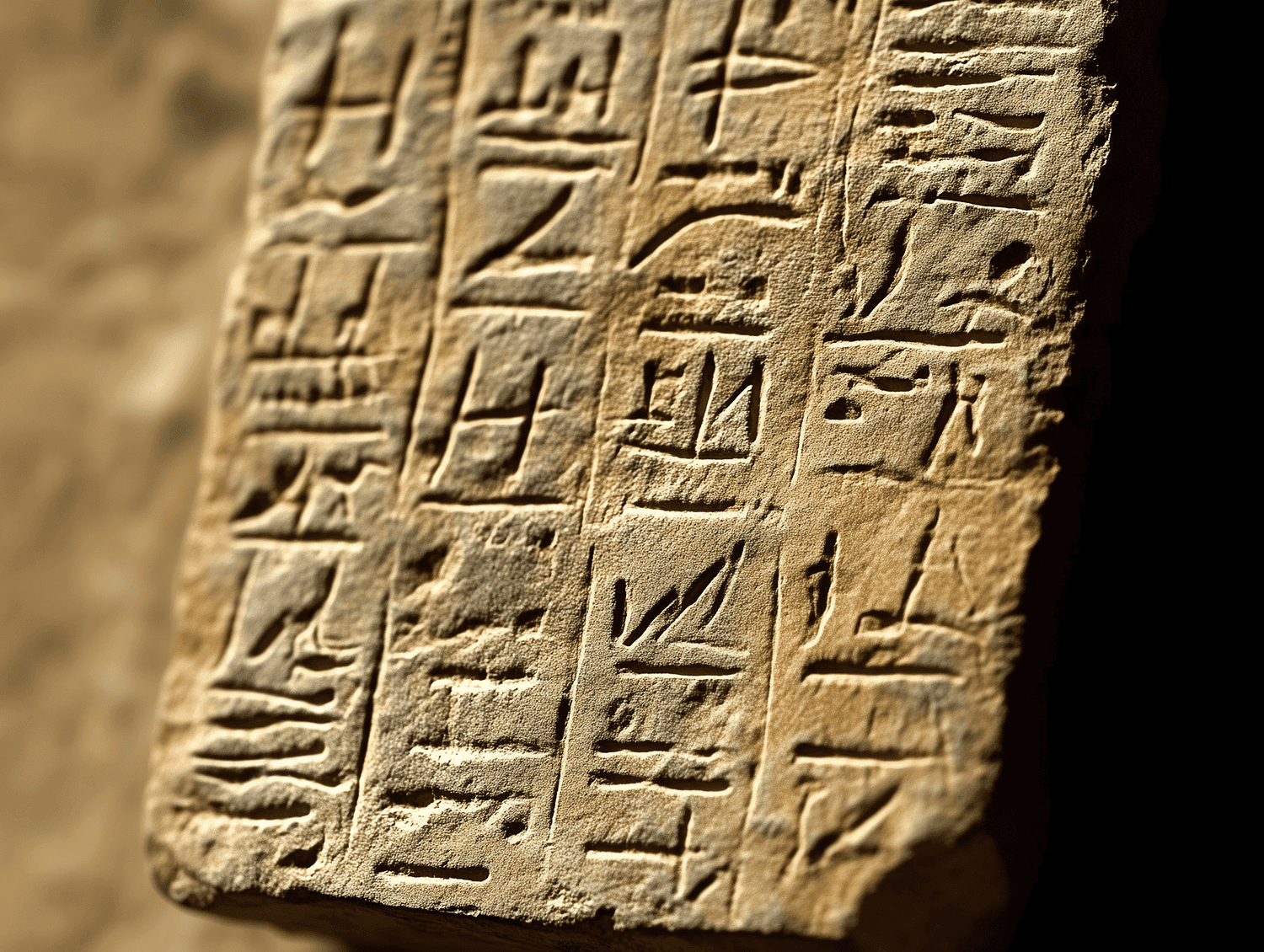

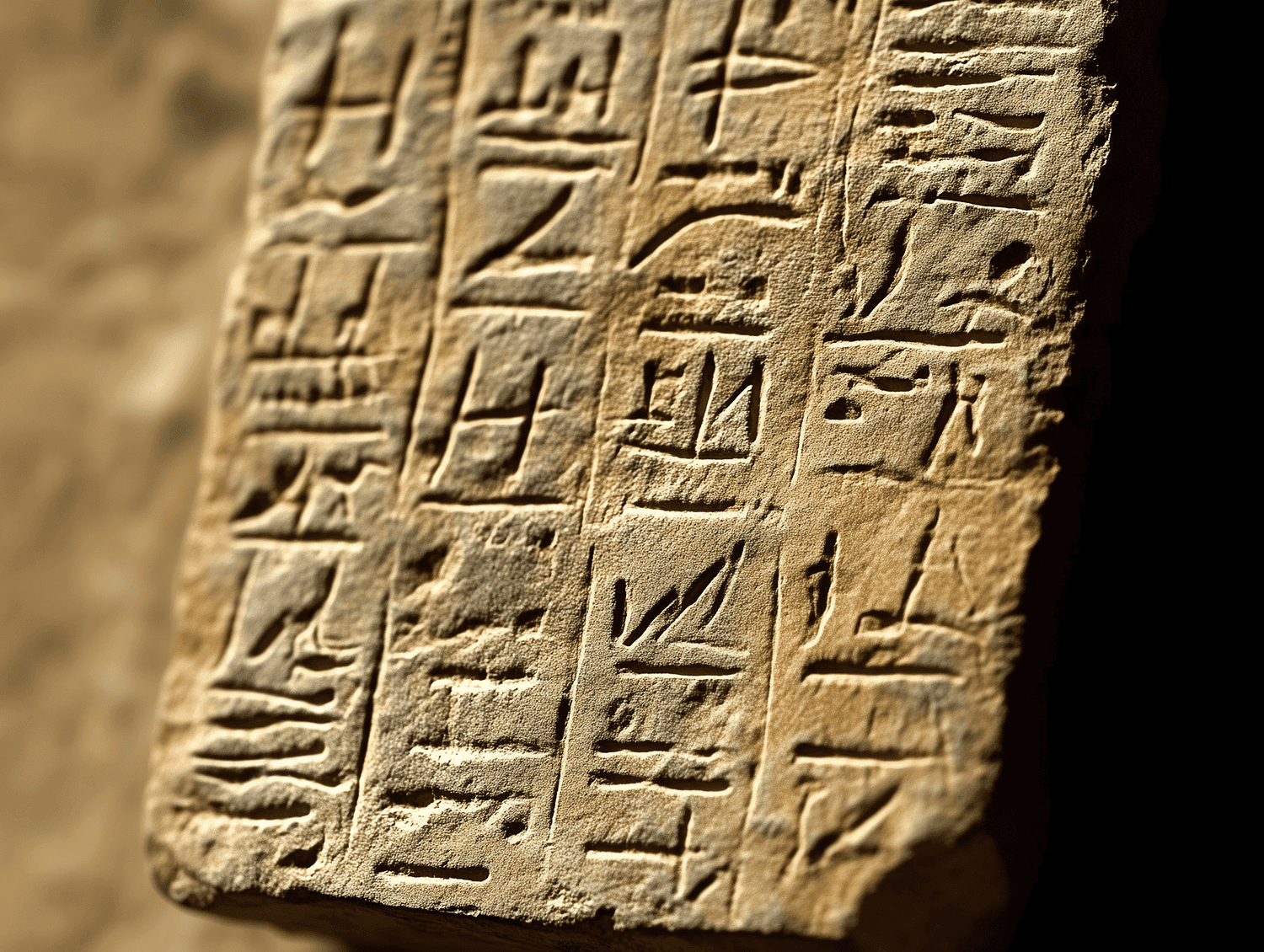

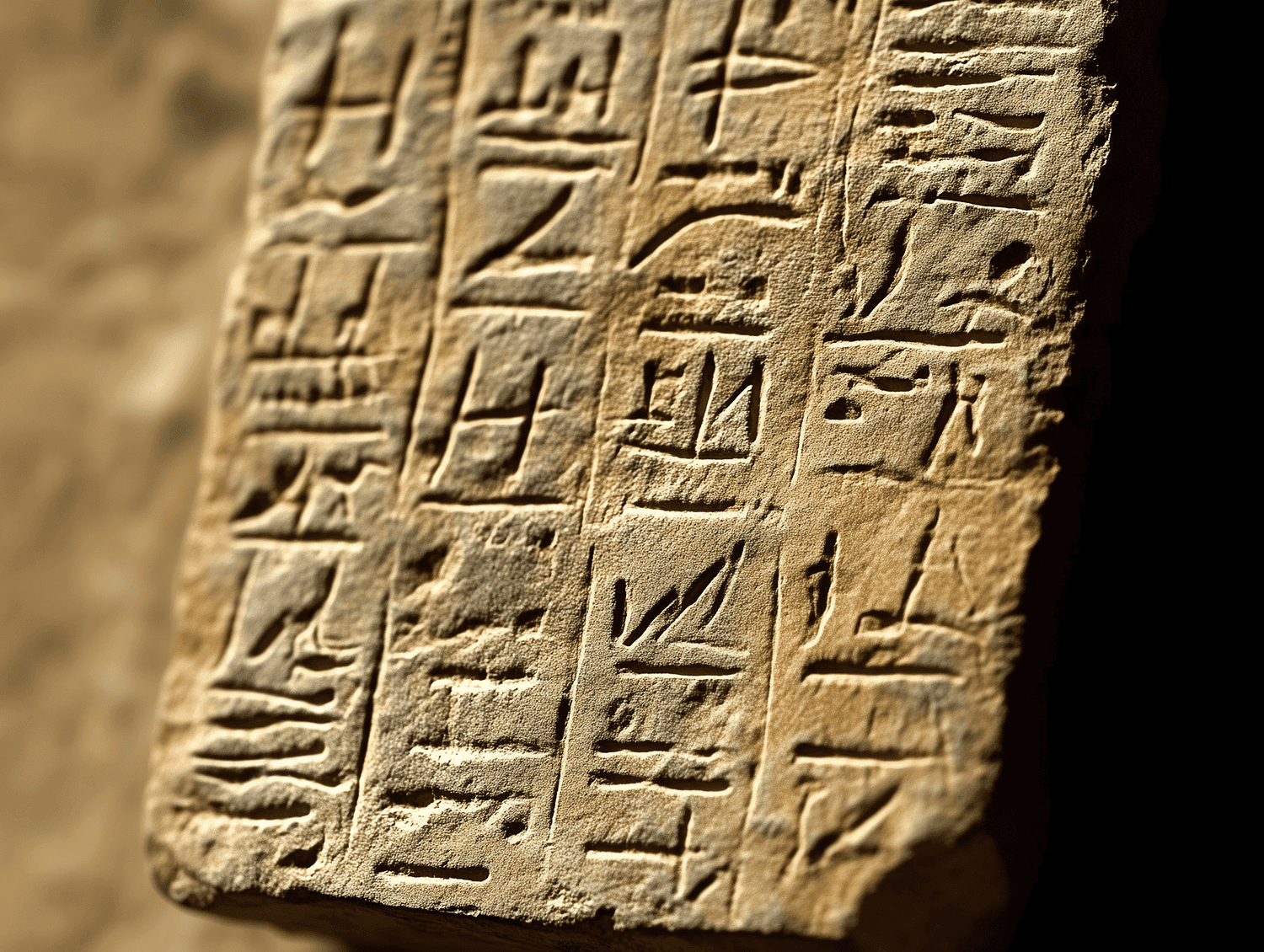

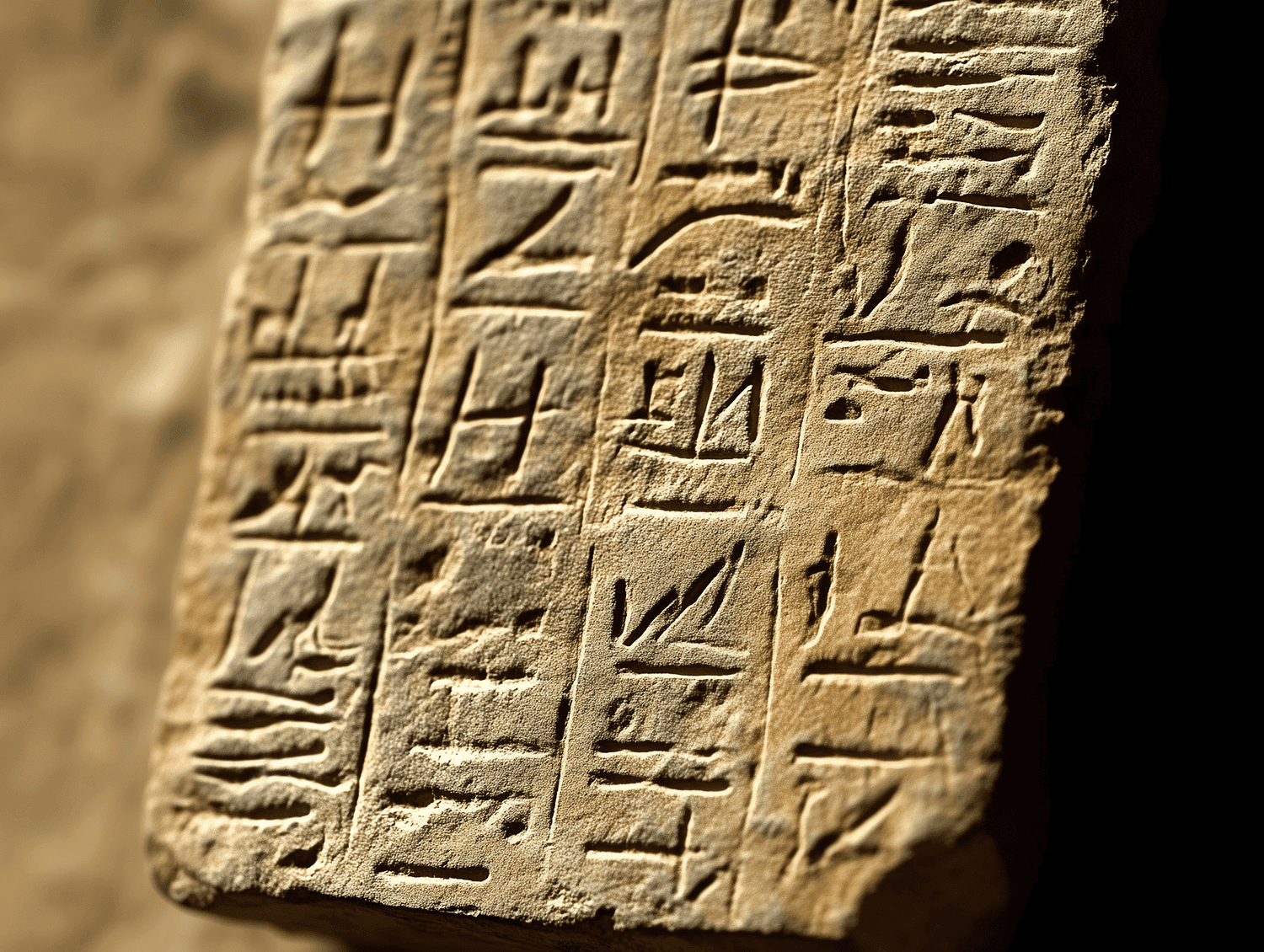

Sumeria and Babylonia

2000 BCE − 1500 BCERecords of the Code of Hammurabi (circa 1754 BCE) indicate that girls were typically married shortly after reaching puberty and childbearing age. It also outlines family provisions, suggesting marriages were arranged while girls were young, with formal relations after they were deemed physically mature[1]. Although the code doesn't specify ages, the Middle Assyrian Laws reference the age of ten in relation to marriage[2].

Ancient Egypt

1500 BCEReligious texts and tomb inscriptions suggest that Egyptian girls were typically married shortly after puberty, usually between 12 and 14 years old, though marriages at ages as young as 8, 9, or 10 were not uncommon[3]. British archaeologist and Egyptologist Joyce Tyldesley notes “there is certainly textual evidence from the Graeco-Roman period for Egyptian girls marrying as young as eight or nine” [4].

Ancient Rome and Greece

1000 BCE − 500 CEBritish archaeologist Joyce Tyldesley notes that “evidence from [ancient] Rome, where female puberty was legally fixed at the age of twelve regardless of the physical development of the girl concerned, indicates that ten- or eleven-year-old brides were not uncommon” [4]. Ancient Greece literature by Aristophanes and Plutarch also depicts young women marrying men who were typically older, reflecting the cultural expectation that women marry shortly after puberty[5a].

Sassanian Empire

224 – 651 CEMiddle Persian civil law, particularly during the Sassanian Empire (which existed contemporaneously with pre-Islamic Arabia), recognized marriage for girls as early as nine, with marital relations beginning when they were considered physically mature, typically between the ages of nine and twelve[5b]. Delaying marriage beyond puberty often resulted in social consequences[5b].

Sumeria and Babylonia

2000 BCE − 1500 BCERecords of the Code of Hammurabi (circa 1754 BCE) indicate that girls were typically married shortly after reaching puberty and childbearing age. It also outlines family provisions, suggesting marriages were arranged while girls were young, with formal relations after they were deemed physically mature[1]. Although the code doesn't specify ages, the Middle Assyrian Laws reference the age of ten in relation to marriage[2].

Ancient Egypt

1500 BCEReligious texts and tomb inscriptions suggest that Egyptian girls were typically married shortly after puberty, usually between 12 and 14 years old, though marriages at ages as young as 8, 9, or 10 were not uncommon[3]. British archaeologist and Egyptologist Joyce Tyldesley notes “there is certainly textual evidence from the Graeco-Roman period for Egyptian girls marrying as young as eight or nine” [4].

Ancient Rome and Greece

1000 BCE − 500 CEBritish archaeologist Joyce Tyldesley notes that “evidence from [ancient] Rome, where female puberty was legally fixed at the age of twelve regardless of the physical development of the girl concerned, indicates that ten- or eleven-year-old brides were not uncommon” [4]. Ancient Greece literature by Aristophanes and Plutarch also depicts young women marrying men who were typically older, reflecting the cultural expectation that women marry shortly after puberty[5a].

Sassanian Empire

224 – 651 CEMiddle Persian civil law, particularly during the Sassanian Empire (which existed contemporaneously with pre-Islamic Arabia), recognized marriage for girls as early as nine, with marital relations beginning when they were considered physically mature, typically between the ages of nine and twelve[5b]. Delaying marriage beyond puberty often resulted in social consequences[5b].

Sumeria and Babylonia

2000 BCE − 1500 BCERecords of the Code of Hammurabi (circa 1754 BCE) indicate that girls were typically married shortly after reaching puberty and childbearing age. It also outlines family provisions, suggesting marriages were arranged while girls were young, with formal relations after they were deemed physically mature[1]. Although the code doesn't specify ages, the Middle Assyrian Laws reference the age of ten in relation to marriage[2].

Ancient Egypt

1500 BCEReligious texts and tomb inscriptions suggest that Egyptian girls were typically married shortly after puberty, usually between 12 and 14 years old, though marriages at ages as young as 8, 9, or 10 were not uncommon[3]. British archaeologist and Egyptologist Joyce Tyldesley notes “there is certainly textual evidence from the Graeco-Roman period for Egyptian girls marrying as young as eight or nine” [4].

Ancient Rome and Greece

1000 BCE − 500 CEBritish archaeologist Joyce Tyldesley notes that “evidence from [ancient] Rome, where female puberty was legally fixed at the age of twelve regardless of the physical development of the girl concerned, indicates that ten- or eleven-year-old brides were not uncommon” [4]. Ancient Greece literature by Aristophanes and Plutarch also depicts young women marrying men who were typically older, reflecting the cultural expectation that women marry shortly after puberty[5a].

Sassanian Empire

224 – 651 CEMiddle Persian civil law, particularly during the Sassanian Empire (which existed contemporaneously with pre-Islamic Arabia), recognized marriage for girls as early as nine, with marital relations beginning when they were considered physically mature, typically between the ages of nine and twelve[5b]. Delaying marriage beyond puberty often resulted in social consequences[5b].

Sumeria and Babylonia

2000 BCE − 1500 BCERecords of the Code of Hammurabi (circa 1754 BCE) indicate that girls were typically married shortly after reaching puberty and childbearing age. It also outlines family provisions, suggesting marriages were arranged while girls were young, with formal relations after they were deemed physically mature[1]. Although the code doesn't specify ages, the Middle Assyrian Laws reference the age of ten in relation to marriage[2].

Ancient Egypt

1500 BCEReligious texts and tomb inscriptions suggest that Egyptian girls were typically married shortly after puberty, usually between 12 and 14 years old, though marriages at ages as young as 8, 9, or 10 were not uncommon[3]. British archaeologist and Egyptologist Joyce Tyldesley notes “there is certainly textual evidence from the Graeco-Roman period for Egyptian girls marrying as young as eight or nine” [4].

Ancient Rome and Greece

1000 BCE − 500 CEBritish archaeologist Joyce Tyldesley notes that “evidence from [ancient] Rome, where female puberty was legally fixed at the age of twelve regardless of the physical development of the girl concerned, indicates that ten- or eleven-year-old brides were not uncommon” [4]. Ancient Greece literature by Aristophanes and Plutarch also depicts young women marrying men who were typically older, reflecting the cultural expectation that women marry shortly after puberty[5a].

Sassanian Empire

224 – 651 CEMiddle Persian civil law, particularly during the Sassanian Empire (which existed contemporaneously with pre-Islamic Arabia), recognized marriage for girls as early as nine, with marital relations beginning when they were considered physically mature, typically between the ages of nine and twelve[5b]. Delaying marriage beyond puberty often resulted in social consequences[5b].

Sumeria and Babylonia

2000 BCE − 1500 BCERecords of the Code of Hammurabi (circa 1754 BCE) indicate that girls were typically married shortly after reaching puberty and childbearing age. It also outlines family provisions, suggesting marriages were arranged while girls were young, with formal relations after they were deemed physically mature[1]. Although the code doesn't specify ages, the Middle Assyrian Laws reference the age of ten in relation to marriage[2].

Ancient Egypt

1500 BCEReligious texts and tomb inscriptions suggest that Egyptian girls were typically married shortly after puberty, usually between 12 and 14 years old, though marriages at ages as young as 8, 9, or 10 were not uncommon[3]. British archaeologist and Egyptologist Joyce Tyldesley notes “there is certainly textual evidence from the Graeco-Roman period for Egyptian girls marrying as young as eight or nine” [4].

Ancient Rome and Greece

1000 BCE − 500 CEBritish archaeologist Joyce Tyldesley notes that “evidence from [ancient] Rome, where female puberty was legally fixed at the age of twelve regardless of the physical development of the girl concerned, indicates that ten- or eleven-year-old brides were not uncommon” [4]. Ancient Greece literature by Aristophanes and Plutarch also depicts young women marrying men who were typically older, reflecting the cultural expectation that women marry shortly after puberty[5a].

Sassanian Empire

224 – 651 CEMiddle Persian civil law, particularly during the Sassanian Empire (which existed contemporaneously with pre-Islamic Arabia), recognized marriage for girls as early as nine, with marital relations beginning when they were considered physically mature, typically between the ages of nine and twelve[5b]. Delaying marriage beyond puberty often resulted in social consequences[5b].

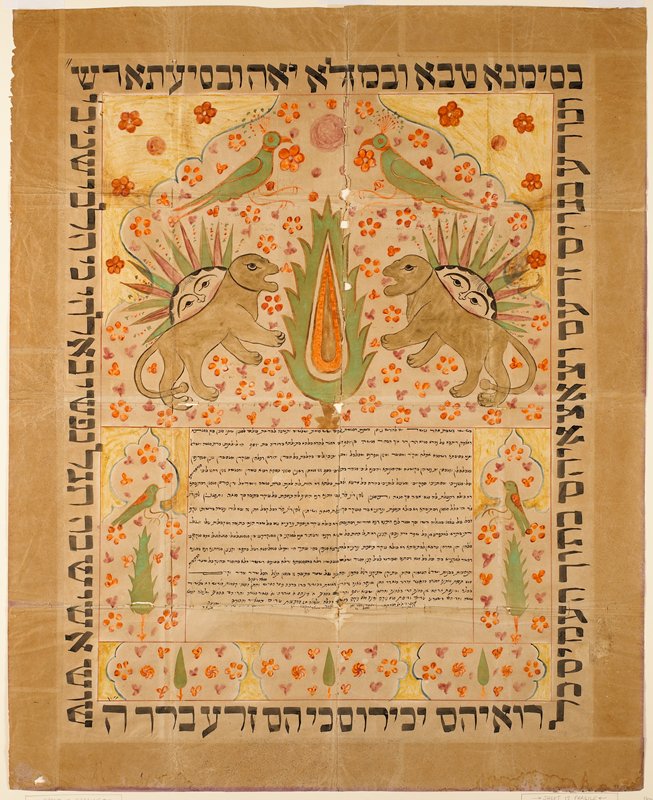

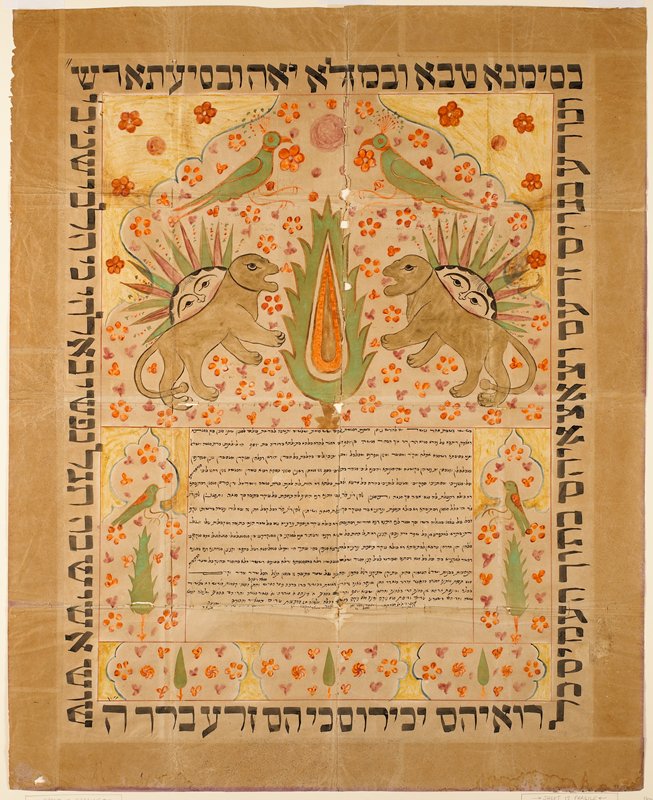

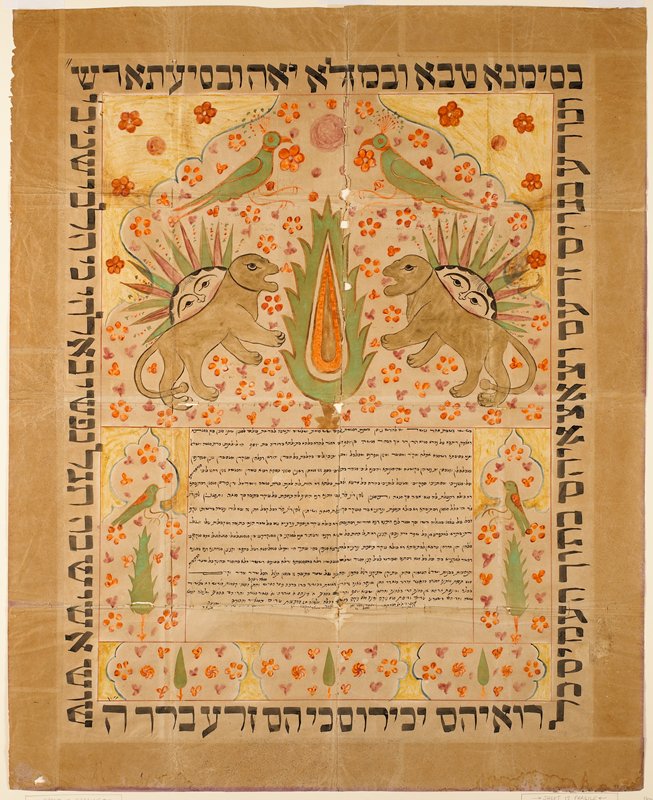

Jewish Marriage Practices

Jewish Marriage Practices

Late Antiquity to Early Medieval Period

Ketubah (Jewish Marriage Contract)

During the Talmudic period (200 CE – 500 CE), young women were typically married shortly after reaching puberty, which aligned with their bat mitzvah, the age at which they were considered both religiously mature and women[6].

During the Talmudic period (200 CE – 500 CE), young women were typically married shortly after reaching puberty, which aligned with their bat mitzvah, the age at which they were considered both religiously mature and women[6].

The Talmud and Mishnah indicate that girls could marry at 12 or 13 years old[7]SOURCE, or even younger in some cases[8]. One of the most debated cases in Jewish tradition involves Rebecca's marriage to Isaac. According to Rabbi Solomon ben Isaac (Rashi), one of the most renowned and foundational Jewish scholars in history, Rebecca was 3 years old when betrothed to Isaac, who was 40. This interpretation stems from a chronological reading of Genesis in the Old Testament, linking her birth to the Binding of Isaac[8]. SOURCE

The Talmud and Mishnah indicate that girls could marry at 12 or 13 years old[7]SOURCE, or even younger in some cases[8]. One of the most debated cases in Jewish tradition involves Rebecca's marriage to Isaac. According to Rabbi Solomon ben Isaac (Rashi), one of the most renowned and foundational Jewish scholars in history, Rebecca was 3 years old when betrothed to Isaac, who was 40. This interpretation stems from a chronological reading of Genesis in the Old Testament, linking her birth to the Binding of Isaac[8]. SOURCE

“… Isaac was then 37 years old. At that period Rebecca was born and he waited until she was fit for marriage — 3 years — and then married her (Seder Olam)” [8]. source

“… Isaac was then 37 years old. At that period Rebecca was born and he waited until she was fit for marriage — 3 years — and then married her (Seder Olam)” [8]. source

Rabbi Solomon ben Isaac (Rashi)

"One of the most influential Jewish commentators in history." — My Jewish Learning

According to the Mishnah, the first major work of rabbinic literature, a father had the authority to arrange a marriage for his daughter while she was still a minor. In discussing the legal implications of such marriages, several passages address the age at which a betrothal or marriage becomes legally valid under Jewish law:

According to the Mishnah, the first major work of rabbinic literature, a father had the authority to arrange a marriage for his daughter while she was still a minor. In discussing the legal implications of such marriages, several passages address the age at which a betrothal or marriage becomes legally valid under Jewish law:

“A girl who is three years and one day old, whose father arranged her betrothal, is betrothed through intercourse… And in a case where the childless husband of a girl three years and one day old dies, if his brother engages in intercourse with her, he acquires her as his wife” [9]. SOURCE

The William Davidson Talmud

Niddah 44b

“A girl who is three years and one day old, whose father arranged her betrothal, is betrothed through intercourse… And in a case where the childless husband of a girl three years and one day old dies, if his brother engages in intercourse with her, he acquires her as his wife” [9]. SOURCE

Niddah 44b

“… with regard to a girl less than three years and one day old, that she is not disqualified by merely entering the wedding canopy. Since there is no legal significance to an act of intercourse with her, there is no legal significance to entering the wedding canopy with her” [10]. SOURCE

The William Davidson Talmud

Yevamot 57b

“… with regard to a girl less than three years and one day old, that she is not disqualified by merely entering the wedding canopy. Since there is no legal significance to an act of intercourse with her, there is no legal significance to entering the wedding canopy with her” [10]. SOURCE

Yevamot 57b

It is important to note that while these legal texts offer insight into historical Jewish law and the framework for marriage, contemporary Jewish communities no longer consider these practices regarding betrothal and marriage applicable and emphasize consent as a fundamental requirement for marriage.

It is important to note that while these legal texts offer insight into historical Jewish law and the framework for marriage, contemporary Jewish communities no longer consider these practices regarding betrothal and marriage applicable and emphasize consent as a fundamental requirement for marriage.

Christian Marriage Practices

Christian Marriage Practices

Late Antiquity to the Late Middle Ages

After the Edict of Milan in 313 CE, Christianity became increasingly institutionalized in the Roman Empire. The Church adopted Roman marriage laws, setting 12 as the age of consent — the age at which girls were considered mature enough for a binding contract.

After the Edict of Milan in 313 CE, Christianity became increasingly institutionalized in the Roman Empire. The Church adopted Roman marriage laws, setting 12 as the age of consent — the age at which girls were considered mature enough for a binding contract.

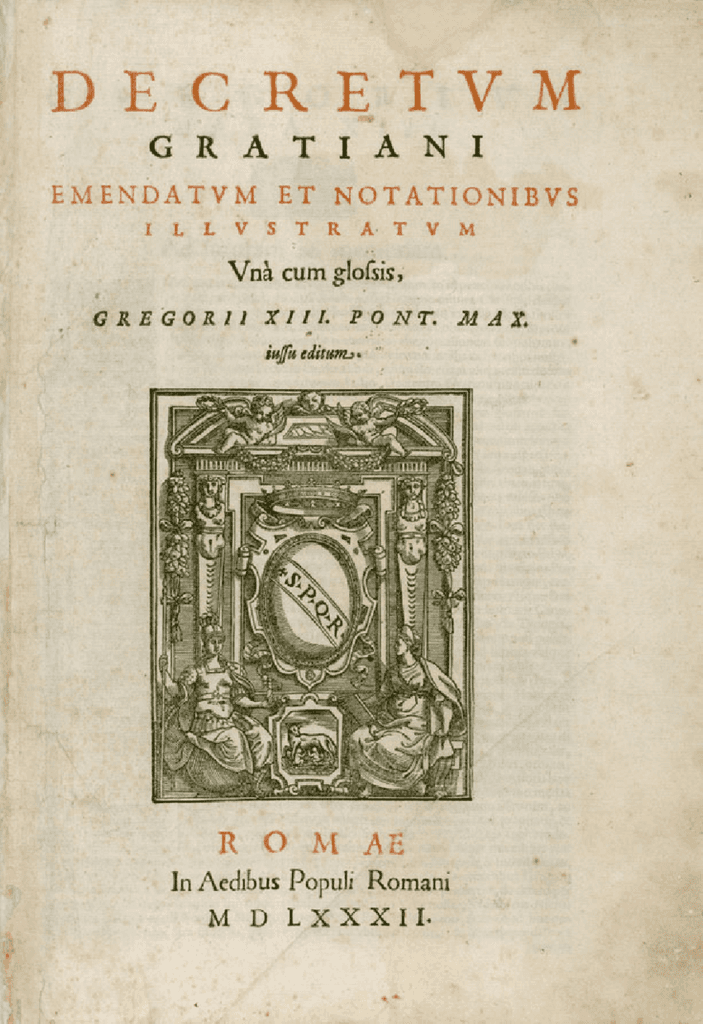

Gratian, a 12th-century jurist and monk known as the father of canon law, compiled and systematized church laws into the Decretum, which became a foundational text. His Decretum (1140) formalized these standards, establishing 12 as the legal marriage age for girls within medieval canon law. This framework shaped Church governance on marriage and continued to influence Western marriage laws into the 19th century[12].

As a result of Gratian’s influence, marriage practices in the late Middle Ages often followed these legal standards. Records from noble families in the 14th and 15th centuries show girls marrying at 12 or 13[13], reflecting the enduring impact of Roman and canon law traditions established by the Decretum.

Canon law also recognized "imperfect marriages," which could be contracted as early as age 7[11].

Gratian, a 12th-century jurist and monk known as the father of canon law, compiled and systematized church laws into the Decretum, which became a foundational text. His Decretum (1140) formalized these standards, establishing 12 as the legal marriage age for girls within medieval canon law. This framework shaped Church governance on marriage and continued to influence Western marriage laws into the 19th century[12].

As a result of Gratian’s influence, marriage practices in the late Middle Ages often followed these legal standards. Records from noble families in the 14th and 15th centuries show girls marrying at 12 or 13[13], reflecting the enduring impact of Roman and canon law traditions established by the Decretum.

Canon law also recognized "imperfect marriages," which could be contracted as early as age 7[11].

The Catholic Encyclopedia

Topic "Civil Marriage"

Gratian’s Decretum (1582)

Large age gaps between spouses were also common. Catholic tradition, including apocryphal texts like The History of Joseph the Carpenter, portrays Joseph as a 90-year-old widower when he married Mary, who was 12 – 14 years old[14]. This view, shared by Eastern Orthodox and Coptic Christians, emphasizes Joseph’s role as a guardian rather than a typical husband, and was a common theme in early Christian and biblical stories.

Large age gaps between spouses were also common. Catholic tradition, including apocryphal texts like The History of Joseph the Carpenter, portrays Joseph as a 90-year-old widower when he married Mary, who was 12 – 14 years old[14]. This view, shared by Eastern Orthodox and Coptic Christians, emphasizes Joseph’s role as a guardian rather than a typical husband, and was a common theme in early Christian and biblical stories.

“Joseph had been a bachelor forty years and was married to his wife forty-nine years until her death, making him near ninety at her death. One year later Mary came into his household and in the third year of her stay Jesus was born, making Joseph ninety-three” [14].

“Joseph had been a bachelor forty years and was married to his wife forty-nine years until her death, making him near ninety at her death. One year later Mary came into his household and in the third year of her stay Jesus was born, making Joseph ninety-three” [14].

History of Joseph the Carpenter

Notable Royal Marriages

Notable Royal Marriages

Henry V

Holy Roman Emperor

Henry V

Holy Roman

Emperor

Age at Marriage: 26

Age at Marriage: 26

Matilda of England

Holy Roman Empress

Matilda of England

Holy Roman

Empress

Age at Betrothal: 8

Age at Marriage: 12

Age at Betrothal: 8

Age at Marriage: 12

Year 1110

Region England / Germany

Year 1110

Region England / Germany

In 1110, Matilda of England, daughter of King Henry I of England, was betrothed to Henry V, the Holy Roman Emperor. At the age of eight, she was sent to Germany to be educated and prepared for her role as empress. Their marriage was formally celebrated in 1114, when Matilda was around 12 years old. As part of the marriage agreement, a substantial dowry was given to King Henry V, and Matilda assumed the title of Holy Roman Empress.

In 1110, Matilda of England, daughter of King Henry I of England, was betrothed to Henry V, the Holy Roman Emperor. At the age of eight, she was sent to Germany to be educated and prepared for her role as empress. Their marriage was formally celebrated in 1114, when Matilda was around 12 years old. As part of the marriage agreement, a substantial dowry was given to King Henry V, and Matilda assumed the title of Holy Roman Empress.

King John of England

King John

of England

Age at Marriage: 34

Age at Marriage: 34

Isabella of Angoulême

Isabella

of Angoulême

Age at Marriage: 10 - 12

Age at Marriage: 10 - 12

Year 1200

Region England / France

Year 1200

Region England / France

King John of England married Isabella of Angoulême in 1200, despite her prior betrothal to Hugh IX of Lusignan. The marriage was politically driven, as John sought to strengthen his claim in France through the union. However, their relationship was strained, and Isabella’s marriage to John contributed to growing tensions with French nobles and the crown.

King John of England married Isabella of Angoulême in 1200, despite her prior betrothal to Hugh IX of Lusignan. The marriage was politically driven, as John sought to strengthen his claim in France through the union. However, their relationship was strained, and Isabella’s marriage to John contributed to growing tensions with French nobles and the crown.

Frederick II

Holy Roman Emperor

Frederick II

Holy Roman

Emperor

Age at Marriage: 31

Age at Marriage: 31

Queen Isabella II

(Yolande) of Jerusalem

Queen Isabella II

(Yolande)

of Jerusalem

Age at Marriage: 13

Age at Marriage: 13

Year 1225

Region Jerusalem

Year 1225

Region Jerusalem

The marriage between Yolande of Jerusalem and Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, was politically motivated, as Frederick aimed to legitimize his claim to the Kingdom of Jerusalem. As part of broader efforts to consolidate Christian control in the Holy Land, Frederick promised to lead a crusade in exchange for the union. However, the marriage was strained, with Frederick marginalizing Yolande and taking control of her kingdom.

The marriage between Yolande of Jerusalem and Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, was politically motivated, as Frederick aimed to legitimize his claim to the Kingdom of Jerusalem. As part of broader efforts to consolidate Christian control in the Holy Land, Frederick promised to lead a crusade in exchange for the union. However, the marriage was strained, with Frederick marginalizing Yolande and taking control of her kingdom.

King Richard II of England

King Richard II

of England

Age at Marriage: 29

Age at Marriage: 29

Queen Isabella of Valois

Queen Isabella

of Valois

Age at Marriage: 6

Age at Marriage: 6

Year 1396

Region England / France

Year 1396

Region England / France

The marriage between Isabella of Valois and King Richard II of England in 1396 was part of a diplomatic effort to establish a lasting peace between England and France during the Hundred Years' War. Known as the Truce of Leulinghem, the marriage symbolized a temporary halt in hostilities, as Isabella was the daughter of King Charles VI of France.

The marriage between Isabella of Valois and King Richard II of England in 1396 was part of a diplomatic effort to establish a lasting peace between England and France during the Hundred Years' War. Known as the Truce of Leulinghem, the marriage symbolized a temporary halt in hostilities, as Isabella was the daughter of King Charles VI of France.

Duke Francesco I Sforza

Sforza Dynasty

Duke Francesco I

Sforza

Sforza Dynasty

Age at Marriage: 29

Age at Marriage: 29

Bianca Maria Visconti

Duchess of Milan

Bianca Maria

Visconti

Duchess of Milan

Age at Betrothal: 5

Age at Marriage: 15

Age at Betrothal: 5

Age at Marriage: 15

Year 1430

Region Italy

Year 1430

Region Italy

The marriage between Duke Francesco I Sforza and Bianca Maria Visconti was a key political alliance in 15th-century Italy. Bianca Maria, betrothed at age 5 and married at 15, was the daughter of Filippo Maria Visconti, the Duke of Milan. This union helped secure Francesco's position as Duke of Milan, merging the influence of the Sforza and Visconti dynasties. The marriage solidified Francesco's control over Milan and played a significant role in shaping the political landscape of northern Italy.

The marriage between Duke Francesco I Sforza and Bianca Maria Visconti was a key political alliance in 15th-century Italy. Bianca Maria, betrothed at age 5 and married at 15, was the daughter of Filippo Maria Visconti, the Duke of Milan. This union helped secure Francesco's position as Duke of Milan, merging the influence of the Sforza and Visconti dynasties. The marriage solidified Francesco's control over Milan and played a significant role in shaping the political landscape of northern Italy.

Charles of Valois

Duke of Berry

Charles of Valois

Duke of Berry

Age at Marriage: 26

Age at Marriage: 26

Queen Joanna

of Castile

Queen Joanna

of Castile

Age at Betrothal: 8

Age at Marriage: 10

Age at Betrothal: 8

Age at Marriage: 10

Year 1470

Region France / Spain

Year 1470

Region France / Spain

The marriage between Charles of Valois, Duke of Berry, and Joanna of Castile was a politically significant union. Joanna was betrothed to Charles at the age of 8 and married by 10. The marriage, however, was short-lived, as Charles died just two years later in 1472. This alliance was part of broader political maneuvering between the French and Spanish crowns, reflecting the dynastic strategies of the time.

The marriage between Charles of Valois, Duke of Berry, and Joanna of Castile was a politically significant union. Joanna was betrothed to Charles at the age of 8 and married by 10. The marriage, however, was short-lived, as Charles died just two years later in 1472. This alliance was part of broader political maneuvering between the French and Spanish crowns, reflecting the dynastic strategies of the time.

Girolamo Riario

Lord of Imola

Girolamo Riario

Lord of Imola

Age at Marriage: 30

Age at Marriage: 30

Lady Caterina Sforza

Countess of Forlì

Lady Caterina

Sforza

Countess of Forlì

Age at Marriage: 10

Age at Marriage: 10

Year 1473

Region Italy

Year 1473

Region Italy

In 1473, Count Girolamo Riario, nephew of Pope Sixtus IV, was initially set to marry Caterina's 11-year-old cousin, Costanza Fogliani, but Costanza's mother refused to allow the marriage to be consummated until she reached the age of 14. Caterina, although only ten years old at the time, agreed to Girolamo's demands and replaced her cousin. The union strengthened the alliance between the papacy and the Sforza family. Caterina later became a powerful figure as Countess of Forlì and Imola.

In 1473, Count Girolamo Riario, nephew of Pope Sixtus IV, was initially set to marry Caterina's 11-year-old cousin, Costanza Fogliani, but Costanza's mother refused to allow the marriage to be consummated until she reached the age of 14. Caterina, although only ten years old at the time, agreed to Girolamo's demands and replaced her cousin. The union strengthened the alliance between the papacy and the Sforza family. Caterina later became a powerful figure as Countess of Forlì and Imola.

King Afonso V of Portugal

King Afonso V

of Portugal

Age at Marriage: 43

Age at Marriage: 43

Queen Joanna of Castile

Queen Joanna

of Castile

Age at Marriage: 13

Age at Marriage: 13

Year 1475

Region Portugal / Spain

Year 1475

Region Portugal / Spain

After Joanna's first husband, Charles of Valois, Duke of Berry, died in 1472, there were a few unsettled arrangements involving French and Burgundian princes. In 1475, Joanna married her maternal uncle, King Afonso V of Portugal, who vowed to defend both her and his claims to the Crown of Castile. This union was part of a broader political struggle for the Castilian throne, with Afonso seeking to assert his own rights through the marriage.

After Joanna's first husband, Charles of Valois, Duke of Berry, died in 1472, there were a few unsettled arrangements involving French and Burgundian princes. In 1475, Joanna married her maternal uncle, King Afonso V of Portugal, who vowed to defend both her and his claims to the Crown of Castile. This union was part of a broader political struggle for the Castilian throne, with Afonso seeking to assert his own rights through the marriage.

Ludovico Sforza

Duke of Milan

Ludovico Sforza

Duke of Milan

Age at Marriage: 29

Age at Marriage: 29

Beatrice d'Este

Duchess of Milan

Beatrice d'Este

Duchess of Milan

Age at Betrothal: 5

Age at Marriage: 15

Age at Betrothal: 5

Age at Marriage: 15

Year 1480

Region Italy

Year 1480

Region Italy

Beatrice d'Este was betrothed to Ludovico Sforza in 1480, when she was five years old, as part of a politically strategic alliance. The marriage itself took place in 1491, and it strengthened Ludovico's position as the de facto ruler of Milan, with the Este family of Ferrara bringing significant political and cultural influence. The marriage was marked by mutual respect and collaboration, with Beatrice playing an important role in Milanese court life.

Beatrice d'Este was betrothed to Ludovico Sforza in 1480, when she was five years old, as part of a politically strategic alliance. The marriage itself took place in 1491, and it strengthened Ludovico's position as the de facto ruler of Milan, with the Este family of Ferrara bringing significant political and cultural influence. The marriage was marked by mutual respect and collaboration, with Beatrice playing an important role in Milanese court life.

Maximilian I

Holy Roman Emperor

Maximilian I

Holy Roman

Emperor

Age at Marriage: 31

Age at Marriage: 31

Duchess Anne

of Brittany

Duchess Anne

of Brittany

Age at Marriage: 13

Age at Marriage: 13

Year 1490

Region France

Year 1490

Region France

Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor, married Duchess Anne of Brittany in 1490. Maximilian was 31, and Anne was 13 at the time of their marriage, which was part of a political alliance aimed at maintaining the independence of Brittany from French control. However, the marriage was annulled under pressure from France, and Anne subsequently married King Charles VIII of France in 1491. This shift in alliances was significant, as it effectively brought Brittany under French rule, marking a key moment in the region's history.

Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor, married Duchess Anne of Brittany in 1490. Maximilian was 31, and Anne was 13 at the time of their marriage, which was part of a political alliance aimed at maintaining the independence of Brittany from French control. However, the marriage was annulled under pressure from France, and Anne subsequently married King Charles VIII of France in 1491. This shift in alliances was significant, as it effectively brought Brittany under French rule, marking a key moment in the region's history.

Francesco II Sforza

Duke of Milan

Francesco II

Sforza

Duke of Milan

Age at Marriage: 37

Age at Marriage: 37

Christina of Denmark, Duchess of Milan

Christina

of Denmark

Duchess of Milan

Christina of Denmark

Duchess of Milan

Age at Marriage: 11

Age at Marriage: 11

Year 1532

Region Italy / Denmark

Year 1532

Region Italy / Denmark

Francesco II Sforza, Duke of Milan, married Christina of Denmark in a politically significant union, particularly during the power struggles over Milan in the Italian Wars. Milan was a contested region, with competing interests from France, the Holy Roman Empire, and Italian rulers. Christina's connections to Denmark and the Habsburg dynasty added political weight to the marriage, influencing the broader European landscape during a time of territorial and dynastic conflicts.

Francesco II Sforza, Duke of Milan, married Christina of Denmark in a politically significant union, particularly during the power struggles over Milan in the Italian Wars. Milan was a contested region, with competing interests from France, the Holy Roman Empire, and Italian rulers. Christina's connections to Denmark and the Habsburg dynasty added political weight to the marriage, influencing the broader European landscape during a time of territorial and dynastic conflicts.

King Philip IV

"Planet King" of Spain

King Philip IV

"Planet King"

of Spain

Age at Marriage: 44

Age at Marriage: 44

Archduchess Maria

Anna of Austria

Archduchess

Maria Anna

of Austria

Age at Marriage: 14

Age at Marriage: 14

Year 1649

Region Spain / Austria

Year 1649

Region Spain / Austria

In 1649, Philip IV of Spain married Maria Anna of Austria, his niece and the daughter of Emperor Ferdinand III of the Holy Roman Empire. This marriage was part of the Habsburg tradition of intermarriage to strengthen political alliances within the dynasty. Philip had previously been married to Elizabeth of France, who had died in 1644, and this second marriage to Maria Anna served to reinforce the bond between the Spanish and Austrian branches of the Habsburg family.

In 1649, Philip IV of Spain married Maria Anna of Austria, his niece and the daughter of Emperor Ferdinand III of the Holy Roman Empire. This marriage was part of the Habsburg tradition of intermarriage to strengthen political alliances within the dynasty. Philip had previously been married to Elizabeth of France, who had died in 1644, and this second marriage to Maria Anna served to reinforce the bond between the Spanish and Austrian branches of the Habsburg family.

King James II of England

King James II

of England

Age at Marriage: 40

Age at Marriage: 40

Queen Mary of Modena

Queen Mary

of Modena

Age at Marriage: 14

Age at Marriage: 14

Year 1673

Region England / Italy

Year 1673

Region England / Italy

In 1673, King James II of England married Mary of Modena, who was 14. This marriage had significant political and religious implications, as it strengthened King James II's ties to Catholic Europe, given Mary’s Italian and Catholic background. The union fueled Protestant opposition in England, eventually contributing to the events that led to the Glorious Revolution.

In 1673, King James II of England married Mary of Modena, who was 14. This marriage had significant political and religious implications, as it strengthened King James II's ties to Catholic Europe, given Mary’s Italian and Catholic background. The union fueled Protestant opposition in England, eventually contributing to the events that led to the Glorious Revolution.

Evolution of Marriage Laws

Evolution of Marriage Laws

Europe and North America

European Cultural Norms

13th – 19th Centuries

The first age-of-consent law in England, established in 1275, made it a crime to “ravish a maiden within age,” interpreted as 12 years old, the same as the legal age for marriage at the time[15]. In 1576, penalties were increased for offenses involving girls under 10. Other European countries, like Italy and Germany, also set 12 as the age of consent in the 16th century. This framework remained until the Offences Against the Person Act of 1875, which raised the age of consent to 13 year[16].

The first age-of-consent law in England, established in 1275, made it a crime to “ravish a maiden within age,” interpreted as 12 years old, the same as the legal age for marriage at the time[15]. In 1576, penalties were increased for offenses involving girls under 10. Other European countries, like Italy and Germany, also set 12 as the age of consent in the 16th century. This framework remained until the Offences Against the Person Act of 1875, which raised the age of consent to 13 year[16].

Enlightenment and Evolving Views

18th – 19th Centuries

During the Enlightenment, new ideas about childhood and education began to influence marriage norms across Europe. Despite the changing attitudes, the legal age for marriage stayed relatively low until the late 19th century. By 1885, the legal age for marriage in the United Kingdom increased from 13 to 16 years[17]. The rise of industrialization and urbanization in France and other European countries also led to declines in early marriages. However, it wasn't until the early 20th century that most European nations standardized the legal age for marriage at 16 or higher[15].

During the Enlightenment, new ideas about childhood and education began to influence marriage norms across Europe. Despite the changing attitudes, the legal age for marriage stayed relatively low until the late 19th century. By 1885, the legal age for marriage in the United Kingdom increased from 13 to 16 years[17]. The rise of industrialization and urbanization in France and other European countries also led to declines in early marriages. However, it wasn't until the early 20th century that most European nations standardized the legal age for marriage at 16 or higher[15].

North American Cultural Norms

17th – 19th Centuries

In colonial America, marriage laws mirrored European traditions, with the legal age of consent for girls set at 12, based on English common law[18]. Economic factors, such as the need to pool labor for family farms, often led to early marriages, particularly in rural areas. As the United States industrialized in the 19th century, Enlightenment ideals slowly began to influence perceptions of childhood and marriage. However, by 1880, most U.S. states still maintained the age of consent between 10 and 12, and Delaware had the lowest age of consent in the U.S. at 7 years old[15].

In colonial America, marriage laws mirrored European traditions, with the legal age of consent for girls set at 12, based on English common law[18]. Economic factors, such as the need to pool labor for family farms, often led to early marriages, particularly in rural areas. As the United States industrialized in the 19th century, Enlightenment ideals slowly began to influence perceptions of childhood and marriage. However, by 1880, most U.S. states still maintained the age of consent between 10 and 12, and Delaware had the lowest age of consent in the U.S. at 7 years old[15].

20th Century Shifts in Marriage Norms

By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, marriage norms shifted dramatically, driven by reforms in education, labor laws, and the development of adolescence as a distinct stage of life. A key turning point came with the “Maiden Tribute” articles in 1885, which exposed the exploitation of young girls in London and led to the raising of the age of consent from 13 to 16[19]. This contributed to broader legal reforms across Europe and North America, where the legal marriage age rose to 16 or 18 by the mid-20th century. Despite this progress, varying biological milestones and social expectations continued to challenge the uniform application of age of consent laws, making it difficult to establish a one-size-fits-all legal framework for marriage and adulthood across different regions[15].

By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, marriage norms shifted dramatically, driven by reforms in education, labor laws, and the development of adolescence as a distinct stage of life. A key turning point came with the “Maiden Tribute” articles in 1885, which exposed the exploitation of young girls in London and led to the raising of the age of consent from 13 to 16[19]. This contributed to broader legal reforms across Europe and North America, where the legal marriage age rose to 16 or 18 by the mid-20th century. Despite this progress, varying biological milestones and social expectations continued to challenge the uniform application of age of consent laws, making it difficult to establish a one-size-fits-all legal framework for marriage and adulthood across different regions[15].

3

A New Dawn for Women

A New Dawn for Women

How Islam Redefined Marriage and Rights

How Islam Redefined Marriage and Rights

Societal Norms in Pre-Islamic Arabia

Societal Norms in Pre-Islamic Arabia

In pre-Islamic Arabia, women had a severely diminished status in society. Renowned American scholar, John Esposito states, “Women... spent much of their lives weakened by pregnancies or tied down with the care of children, [and] could easily become liabilities to a tribe.” This lack of mobility and perceived strength compared to men contributed to practices like female infanticide[1].

In pre-Islamic Arabia, women had a severely diminished status in society. Renowned American scholar, John Esposito states, “Women... spent much of their lives weakened by pregnancies or tied down with the care of children, [and] could easily become liabilities to a tribe.” This lack of mobility and perceived strength compared to men contributed to practices like female infanticide[1].

Marriage customs further entrenched this inequality with the "ba'l" form of marriage, where a woman was essentially purchased and became the property of her husband. In such marriages, “the woman's status was considerably lowered since she lost her right to choose and dismiss her mate"[1]. The term ba'l itself, meaning “lord” or “owner,” reflected the oppressive power men held over their wives, turning them into commodities. The right to unlimited polygamy allowed men to acquire multiple wives through purchase or capture, the latter being a common practice in Byzantium, Persia, Syria, and Arabia[1].

Marriage customs further entrenched this inequality with the "ba'l" form of marriage, where a woman was essentially purchased and became the property of her husband. In such marriages, “the woman's status was considerably lowered since she lost her right to choose and dismiss her mate"[1]. The term ba'l itself, meaning “lord” or “owner,” reflected the oppressive power men held over their wives, turning them into commodities. The right to unlimited polygamy allowed men to acquire multiple wives through purchase or capture, the latter being a common practice in Byzantium, Persia, Syria, and Arabia[1].

A woman’s value was largely tied to the bride-price that her family received during her marriage. This payment, made to the father, reflected the transactional nature of marriage, where the exchange was primarily between men. The bride herself had little say, and her role in the transaction underscored her status as a dependent, with her value measured by the wealth transferred through the marriage arrangement[1].

Women were also often denied the right to inherit property due to the need to preserve tribal wealth and continuity. Since women would eventually become part of their husband’s tribe after marriage, and any inheritance they received would transfer wealth outside their birth tribe[1]. This practice reinforced their dependence on male relatives and further limited their autonomy in society.

A woman’s value was largely tied to the bride-price that her family received during her marriage. This payment, made to the father, reflected the transactional nature of marriage, where the exchange was primarily between men. The bride herself had little say, and her role in the transaction underscored her status as a dependent, with her value measured by the wealth transferred through the marriage arrangement[1].

Women were also often denied the right to inherit property due to the need to preserve tribal wealth and continuity. Since women would eventually become part of their husband’s tribe after marriage, and any inheritance they received would transfer wealth outside their birth tribe[1]. This practice reinforced their dependence on male relatives and further limited their autonomy in society.

Islamic Reforms

Islamic Reforms

Fairness, Autonomy, and Legal Protections for Women

Fairness, Autonomy, and Legal Protections for Women

Islam introduced a revolutionary shift by framing marriage as a binding contract between two consenting, mature individuals, each with rights and obligations[1].

Islam introduced a revolutionary shift by framing marriage as a binding contract between two consenting, mature individuals, each with rights and obligations[1].

Islamic law emphasized that true consent to marriage must be based on an individual’s physical, intellectual, and emotional maturity — qualities a minor cannot possess. This is supported by the verse:

Islamic law emphasized that true consent to marriage must be based on an individual’s physical, intellectual, and emotional maturity — qualities a minor cannot possess. This is supported by the verse:

“O believers! It is not permissible for you to inherit women against their will, or mistreat them to make them return some of the dowry.”

“O believers! It is not permissible for you to inherit women against their will, or mistreat them to make them return some of the dowry.”

The reference to ‘women’ reflects the expectation of physical and intellectual readiness, affirming that consent must be voluntary and based on the individual’s capacity to understand marital responsibilities.

The reference to ‘women’ reflects the expectation of physical and intellectual readiness, affirming that consent must be voluntary and based on the individual’s capacity to understand marital responsibilities.

While Islamic law set puberty as the minimum threshold for marriage, it introduced a comprehensive approach — marriage was not merely a matter of biological readiness, but about an individual's capability to handle the broader responsibilities. As reflected in Surah An-Nisa, where the competence of orphans is tested before they are entrusted with their wealth, readiness extended beyond physical markers:

While Islamic law set puberty as the minimum threshold for marriage, it introduced a comprehensive approach — marriage was not merely a matter of biological readiness, but about an individual's capability to handle the broader responsibilities. As reflected in Surah An-Nisa, where the competence of orphans is tested before they are entrusted with their wealth, readiness extended beyond physical markers:

“Test the competence of the orphans until they reach a marriageable age. Then if you feel they are capable of sound judgment, return their wealth to them.”

“Test the competence of the orphans until they reach a marriageable age. Then if you feel they are capable of sound judgment, return their wealth to them.”

Alongside the requirements for consent and maturity in marriage, Prophet Muhammad A also introduced legal protections for women, including the right to dowry, inheritance, and divorce. These provisions ensured women had greater autonomy and the ability to seek legal recourse in cases of disputes, fundamentally improving their status and rights within society.

Alongside the requirements for consent and maturity in marriage, Prophet Muhammad A also introduced legal protections for women, including the right to dowry, inheritance, and divorce. These provisions ensured women had greater autonomy and the ability to seek legal recourse in cases of disputes, fundamentally improving their status and rights within society.

Overview of Key Women's Rights

Overview of Key Women's Rights

Right to Consent

Status Quo In pre-Islamic Arabia, women had little agency in marriage matters.

Reform Islam introduced the requirement that women must consent to marriage. Islamic law mandated that the woman’s consent is indispensable to validate a marriage contract.

Reference “O you who have believed, it is not lawful for you to inherit women by compulsion”

Right to Dowry (Mahr)

Status Quo From ancient Rome and Greece to medieval Europe, dowry or bride-price was given either to the bride's family or to the groom, but never to the bride.

Reform Islam made it mandatory for the groom to give dowry directly to the bride instead, ensuring her financial security and independence within the marriage.

Reference “And give the women [upon marriage] their [bridal] gifts graciously.”

Right to Divorce

Status Quo In many pre-Islamic and medieval societies, men predominantly controlled divorce, denying women the right to initiate separation independently.

Reform Prophet Muhammad A granted women the right to seek divorce through khula, ensuring women were not trapped in unhappy marriages.

Reference “… there is no blame if the wife compensates [returns the dowry] to the husband to obtain divorce.”

Right to Keep Maiden Name

Status Quo Wives taking their husband's name was generally uncommon, but became prominent in medieval Europe under coverture, where a woman's legal rights were absorbed by her husband.

Reform Islam allowed women to retain their maiden names, preserving their identity, lineage, and independent status.

Reference The Prophet’s A wives retained their family names after marriage, setting a lasting precedent.

Right to Financial Maintenance

Status Quo In pre-Islamic society, husbands had no legal obligation to provide for their wives, leaving many women vulnerable.

Reform Islam made it mandatory for husbands to financially support their wives, regardless of the wife's wealth.

Reference “Men are the caretakers of women, as men have been provisioned by Allah over women and tasked with supporting them financially.”

Polygamy and Restrictions

Status Quo In ancient Greece, Rome, and pre-Islamic Arabia, men could have multiple unrestricted relationships through marriage, courtesans, or concubines.

Reform Islamic reforms limited men to a maximum of four wives, provided they were all given equal rights and treated fairly. The Quran cautions:

Reference “But if you fear that you will not be just, then [marry only] one, this way you are less likely to commit injustice.”

Right to Privacy in Marriage

Status Quo Ancient Greece, Rome, pre-Islamic Arabia, and medieval Europe often treated personal aspects of marriage as public matters, offering little protection for women's privacy.

Reform Islam emphasized the sanctity of marriage and discouraged sharing private marital matters.

Reference “The most wicked among the people in the sight of Allah is one who goes to his wife and she comes to him, and then he divulges her secret.”

Right to Kind Treatment

Status Quo Women were often viewed as their husbands' property, subject to harsh treatment in ancient Greece, Rome, pre-Islamic Arabia, and medieval Europe.

Reform Islam emphasized kindness and respect in marriage. In his Farewell Sermon, the Prophet A reminded, “You have rights over your women, but they also have rights over you.”

Reference “The best of you is the one who is best to his wife.”

Right to Have Witnesses

Status Quo In ancient Rome, Greece, and pre-Islamic Arabia, marriages often lacked witnesses, leaving women vulnerable to disputes over validity and rights.

Reform Islam introduced the requirement of two witnesses, ensuring transparency and transforming marriage into a publicly recognized contract.

Reference “… one man and two women of your choice will witness —so if one of the women forgets the other may remind her.”

Right to Inheritance

Status Quo Prior to Islam, women were generally excluded from inheritance, as property passed through male heirs.

Reform Islamic inheritance laws granted women a fixed share, with their financial care being the responsibility of husbands or immediate male relatives.

Reference “For women there is a share in what their parents and close relatives leave — whether it is little or much. These are obligatory shares.”

Right to an Education

Status Quo Education or seeking knowledge for women was not prioritized in pre-Islamic Arabia.

Reform Prophet Muhammad A emphasized equal access to knowledge for both men and women.

Reference “Seeking knowledge is an obligation upon every Muslim.”

Protection from Female Infanticide

Status Quo Pre-Islamic Arabia practiced female infanticide due to cultural biases against daughters.

Reform Islam prohibited this practice, emphasizing the equal value of all children.

Reference “And when baby girls, buried alive, are asked, for what crime they were put to death.”

Right to Consent

Status Quo In pre-Islamic Arabia, women had little agency in marriage matters.

Reform Islam introduced the requirement that women must consent to marriage. Islamic law mandated that the woman’s consent is indispensable to validate a marriage contract.

Reference “O you who have believed, it is not lawful for you to inherit women by compulsion”

Right to Dowry (Mahr)

Status Quo From ancient Rome and Greece to medieval Europe, dowry or bride-price was given either to the bride's family or to the groom, but never to the bride.

Reform Islam made it mandatory for the groom to give dowry directly to the bride instead, ensuring her financial security and independence within the marriage.

Reference “And give the women [upon marriage] their [bridal] gifts graciously.”

Right to Divorce

Status Quo In many pre-Islamic and medieval societies, men predominantly controlled divorce, denying women the right to initiate separation independently.

Reform Prophet Muhammad A granted women the right to seek divorce through khula, ensuring women were not trapped in unhappy marriages.

Reference “… there is no blame if the wife compensates [returns the dowry] to the husband to obtain divorce.”

Right to Keep Maiden Name

Status Quo Wives taking their husband's name was generally uncommon, but became prominent in medieval Europe under coverture, where a woman's legal rights were absorbed by her husband.

Reform Islam allowed women to retain their maiden names, preserving their identity, lineage, and independent status.

Reference The Prophet’s A wives retained their family names after marriage, setting a lasting precedent.

Right to Financial Maintenance

Status Quo In pre-Islamic society, husbands had no legal obligation to provide for their wives, leaving many women vulnerable.

Reform Islam made it mandatory for husbands to financially support their wives, regardless of the wife's wealth.

Reference “Men are the caretakers of women, as men have been provisioned by Allah over women and tasked with supporting them financially.”

Polygamy and Restrictions

Status Quo In ancient Greece, Rome, and pre-Islamic Arabia, men could have multiple unrestricted relationships through marriage, courtesans, or concubines.

Reform Islamic reforms limited men to a maximum of four wives, provided they were all given equal rights and treated fairly. The Quran cautions:

Reference “But if you fear that you will not be just, then [marry only] one, this way you are less likely to commit injustice.”

Right to Privacy in Marriage

Status Quo Ancient Greece, Rome, pre-Islamic Arabia, and medieval Europe often treated personal aspects of marriage as public matters, offering little protection for women's privacy.

Reform Islam emphasized the sanctity of marriage and discouraged sharing private marital matters.

Reference “The most wicked among the people in the sight of Allah is one who goes to his wife and she comes to him, and then he divulges her secret.”

Right to Kind Treatment

Status Quo Women were often viewed as their husbands' property, subject to harsh treatment in ancient Greece, Rome, pre-Islamic Arabia, and medieval Europe.

Reform Islam emphasized kindness and respect in marriage. In his Farewell Sermon, the Prophet A reminded, “You have rights over your women, but they also have rights over you.”

Reference “The best of you is the one who is best to his wife.”

Right to Have Witnesses

Status Quo In ancient Rome, Greece, and pre-Islamic Arabia, marriages often lacked witnesses, leaving women vulnerable to disputes over validity and rights.

Reform Islam introduced the requirement of two witnesses, ensuring transparency and transforming marriage into a publicly recognized contract.

Reference “… one man and two women of your choice will witness —so if one of the women forgets the other may remind her.”

Right to Inheritance

Status Quo Prior to Islam, women were generally excluded from inheritance, as property passed through male heirs.

Reform Islamic inheritance laws granted women a fixed share, with their financial care being the responsibility of husbands or immediate male relatives.

Reference “For women there is a share in what their parents and close relatives leave — whether it is little or much. These are obligatory shares.”

Right to an Education

Status Quo Education or seeking knowledge for women was not prioritized in pre-Islamic Arabia.

Reform Prophet Muhammad A emphasized equal access to knowledge for both men and women.

Reference “Seeking knowledge is an obligation upon every Muslim.”

Protection from Female Infanticide

Status Quo Pre-Islamic Arabia practiced female infanticide due to cultural biases against daughters.

Reform Islam prohibited this practice, emphasizing the equal value of all children.

Reference “And when baby girls, buried alive, are asked, for what crime they were put to death.”

Right to Consent

Status Quo In pre-Islamic Arabia, women had little agency in marriage matters.

Reform Islam introduced the requirement that women must consent to marriage. Islamic law mandated that the woman’s consent is indispensable to validate a marriage contract.

Reference “O you who have believed, it is not lawful for you to inherit women by compulsion”

Right to Dowry (Mahr)

Status Quo From ancient Rome and Greece to medieval Europe, dowry or bride-price was given either to the bride's family or to the groom, but never to the bride.

Reform Islam made it mandatory for the groom to give dowry directly to the bride instead, ensuring her financial security and independence within the marriage.

Reference “And give the women [upon marriage] their [bridal] gifts graciously.”

Right to Divorce

Status Quo In many pre-Islamic and medieval societies, men predominantly controlled divorce, denying women the right to initiate separation independently.

Reform Prophet Muhammad A granted women the right to seek divorce through khula, ensuring women were not trapped in unhappy marriages.

Reference “… there is no blame if the wife compensates [returns the dowry] to the husband to obtain divorce.”

Right to Keep Maiden Name

Status Quo Wives taking their husband's name was generally uncommon, but became prominent in medieval Europe under coverture, where a woman's legal rights were absorbed by her husband.

Reform Islam allowed women to retain their maiden names, preserving their identity, lineage, and independent status.

Reference The Prophet’s A wives retained their family names after marriage, setting a lasting precedent.

Right to Financial Maintenance

Status Quo In pre-Islamic society, husbands had no legal obligation to provide for their wives, leaving many women vulnerable.

Reform Islam made it mandatory for husbands to financially support their wives, regardless of the wife's wealth.

Reference “Men are the caretakers of women, as men have been provisioned by Allah over women and tasked with supporting them financially.”

Polygamy and Restrictions

Status Quo In ancient Greece, Rome, and pre-Islamic Arabia, men could have multiple unrestricted relationships through marriage, courtesans, or concubines.

Reform Islamic reforms limited men to a maximum of four wives, provided they were all given equal rights and treated fairly. The Quran cautions:

Reference “But if you fear that you will not be just, then [marry only] one, this way you are less likely to commit injustice.”

Right to Privacy in Marriage

Status Quo Ancient Greece, Rome, pre-Islamic Arabia, and medieval Europe often treated personal aspects of marriage as public matters, offering little protection for women's privacy.

Reform Islam emphasized the sanctity of marriage and discouraged sharing private marital matters.

Reference “The most wicked among the people in the sight of Allah is one who goes to his wife and she comes to him, and then he divulges her secret.”

Right to Kind Treatment

Status Quo Women were often viewed as their husbands' property, subject to harsh treatment in ancient Greece, Rome, pre-Islamic Arabia, and medieval Europe.

Reform Islam emphasized kindness and respect in marriage. In his Farewell Sermon, the Prophet A reminded, “You have rights over your women, but they also have rights over you.”

Reference “The best of you is the one who is best to his wife.”

Right to Have Witnesses

Status Quo In ancient Rome, Greece, and pre-Islamic Arabia, marriages often lacked witnesses, leaving women vulnerable to disputes over validity and rights.

Reform Islam introduced the requirement of two witnesses, ensuring transparency and transforming marriage into a publicly recognized contract.

Reference “… one man and two women of your choice will witness —so if one of the women forgets the other may remind her.”

Right to Inheritance

Status Quo Prior to Islam, women were generally excluded from inheritance, as property passed through male heirs.

Reform Islamic inheritance laws granted women a fixed share, with their financial care being the responsibility of husbands or immediate male relatives.

Reference “For women there is a share in what their parents and close relatives leave — whether it is little or much. These are obligatory shares.”

Right to an Education

Status Quo Education or seeking knowledge for women was not prioritized in pre-Islamic Arabia.

Reform Prophet Muhammad A emphasized equal access to knowledge for both men and women.

Reference “Seeking knowledge is an obligation upon every Muslim.”

Protection from Female Infanticide

Status Quo Pre-Islamic Arabia practiced female infanticide due to cultural biases against daughters.

Reform Islam prohibited this practice, emphasizing the equal value of all children.

Reference “And when baby girls, buried alive, are asked, for what crime they were put to death.”

Right to Consent

Status Quo In pre-Islamic Arabia, women had little agency in marriage matters.

Reform Islam introduced the requirement that women must consent to marriage. Islamic law mandated that the woman’s consent is indispensable to validate a marriage contract.

Reference “O you who have believed, it is not lawful for you to inherit women by compulsion”

Right to Dowry (Mahr)

Status Quo From ancient Rome and Greece to medieval Europe, dowry or bride-price was given either to the bride's family or to the groom, but never to the bride.

Reform Islam made it mandatory for the groom to give dowry directly to the bride instead, ensuring her financial security and independence within the marriage.

Reference “And give the women [upon marriage] their [bridal] gifts graciously.”

Right to Divorce

Status Quo In many pre-Islamic and medieval societies, men predominantly controlled divorce, denying women the right to initiate separation independently.

Reform Prophet Muhammad A granted women the right to seek divorce through khula, ensuring women were not trapped in unhappy marriages.

Reference “… there is no blame if the wife compensates [returns the dowry] to the husband to obtain divorce.”

Right to Keep Maiden Name

Status Quo Wives taking their husband's name was generally uncommon, but became prominent in medieval Europe under coverture, where a woman's legal rights were absorbed by her husband.

Reform Islam allowed women to retain their maiden names, preserving their identity, lineage, and independent status.

Reference The Prophet’s A wives retained their family names after marriage, setting a lasting precedent.

Right to Financial Maintenance

Status Quo In pre-Islamic society, husbands had no legal obligation to provide for their wives, leaving many women vulnerable.

Reform Islam made it mandatory for husbands to financially support their wives, regardless of the wife's wealth.

Reference “Men are the caretakers of women, as men have been provisioned by Allah over women and tasked with supporting them financially.”

Polygamy and Restrictions

Status Quo In ancient Greece, Rome, and pre-Islamic Arabia, men could have multiple unrestricted relationships through marriage, courtesans, or concubines.

Reform Islamic reforms limited men to a maximum of four wives, provided they were all given equal rights and treated fairly. The Quran cautions:

Reference “But if you fear that you will not be just, then [marry only] one, this way you are less likely to commit injustice.”

Right to Privacy in Marriage

Status Quo Ancient Greece, Rome, pre-Islamic Arabia, and medieval Europe often treated personal aspects of marriage as public matters, offering little protection for women's privacy.

Reform Islam emphasized the sanctity of marriage and discouraged sharing private marital matters.

Reference “The most wicked among the people in the sight of Allah is one who goes to his wife and she comes to him, and then he divulges her secret.”

Right to Kind Treatment

Status Quo Women were often viewed as their husbands' property, subject to harsh treatment in ancient Greece, Rome, pre-Islamic Arabia, and medieval Europe.

Reform Islam emphasized kindness and respect in marriage. In his Farewell Sermon, the Prophet A reminded, “You have rights over your women, but they also have rights over you.”

Reference “The best of you is the one who is best to his wife.”

Right to Have Witnesses

Status Quo In ancient Rome, Greece, and pre-Islamic Arabia, marriages often lacked witnesses, leaving women vulnerable to disputes over validity and rights.

Reform Islam introduced the requirement of two witnesses, ensuring transparency and transforming marriage into a publicly recognized contract.